The Heart of Great Bay: Field Notes from a Doyle Fellow

The Doyle Undergraduate Fellowship gives students the opportunity to step beyond the classroom and into the living laboratories of New Hampshire’s coast, working alongside scientists on research that directly supports healthy coastal ecosystems and economies.

The fellowship is now open for applications, inviting a new cohort of curious, motivated undergraduates to gain hands-on experience in fields ranging from estuarine ecology to coastal resilience.

To celebrate the impact of this fellowship, we’re sharing a reflection from last year's Science Communications Doyle Fellow, Talia Katreczko, who captured a day in the life at the Jackson Estuarine Laboratory, or as they call it, the heart of Great Bay. Their story offers a glimpse of what the fellowship feels like in action: muddy boots, salty air, and discovery around every corner.

Nestled deep in the rocky coast of New Hampshire’s Great Bay Estuary, the Jackson Estuarine Laboratory (JEL) is more than just a coastal research station, it’s a beating heart of ecological discovery. If you were to trace a mirrored image over the bay region, JEL would land right at its center. This lab, surrounded by rockweed-covered shorelines and the brackish rhythm of tidal waters, is a hub of biological convergence and scientific exploration.

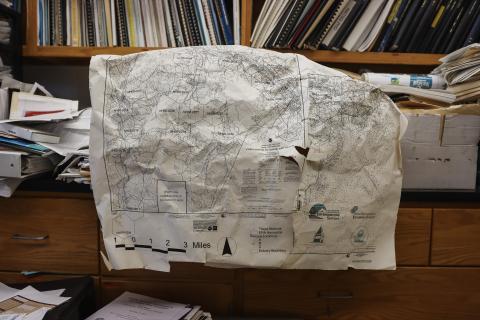

On a quiet morning, with sunlight filtering gently across the mudflats, the lab hums to life. From the entrance, a faint buzzing, a whisper of research equipment underway, draws visitors inward. Shelves lined with marine treasures offer a preview of what’s to come: aged oyster shells, algae field guides, and maps that fold and unfold the many mysteries of the bay.

The hallways fork into stairs, each leading to research spaces that feel embedded in the landscape itself. Floor-to-ceiling windows reveal panoramic views of the estuary, blurring the line between observation and immersion. The scent of salt, the gleam of lab equipment, and the promise of discovery fill the air.

The lights are off, so I assume most people haven’t arrived yet. As I meander towards the humming sound, I notice the bay just outside.

Layers of research and experimentation envelop the objects within; someone turns the light on for me and I’m able to get a closer look.

Upstairs, Doyle Fellow Gabrielle Levine is elbows-deep in seaweed, literally. She’s contributing to the Great Bay Bottom Habitat Monitoring Project, a long-term effort to understand how environmental factors, nutrient dynamics and species competition shape this vital ecosystem.

Gabrielle collects large clumps of rockweed, kelp, and other common Great Bay seaweed from a walk-in freezer.

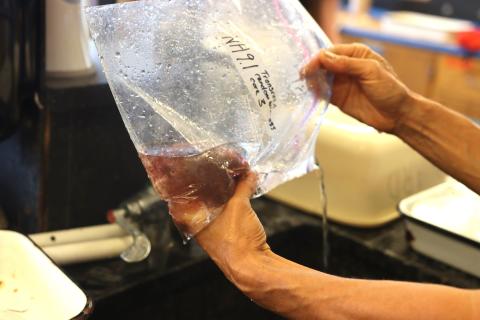

Her work involves sorting these large clumps of various-colored seaweeds, a task made more complex by the deceptive hues of wet algae. These are collected along the bottom of Great Bay to determine their nutrient content and whether or not they are competing with the eelgrass population, a keystone species in estuarine environments. The samples are sourced from randomly-placed transect surveys along the bay floor.

Any eelgrass collected is measured, dried in a lab oven, and later sent out for chemical analysis.

I wander outside to the back of JEL and find an equipment stash amongst the forest. I stumble across the ‘boneyard’: a pile of in-use traps, nets, and other devices.

Sonds soak up the sun as they await deployment. A sond is a scientific instrument used to measure water quality parameters such as temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, pH, and turbidity. Powered by solar energy, these devices play a crucial role in monitoring aquatic ecosystems, offering researchers real-time data that helps track environmental health, detect pollution, and guide conservation efforts.

Most of the equipment at JEL is used for several different projects.

Just down the slope toward the dock, a row of fiberglass holding tanks sit in waiting, some filled for experiments, others cleaned and empty, their algae-stained interiors hinting at past trials. These tanks play a role in one of the lab’s major initiatives: eelgrass restoration.

Doyle Fellow Matt Allen is assisting that work, testing a method of replanting eelgrass in the expansive mudflats of the estuary. His team collects healthy eelgrass from the New Hampshire coastline and weaves it into burlap mats, which are then affixed to modified lobster traps. These structures are hand-placed by divers in restoration zones, where they serve as anchors for new growth.

Matt grew up fishing near the bay, and decided to investigate the changes happening to eelgrass beds that he noticed during his studies at UNH. His work on this project has broadened his understanding of how different organizations are working together to solve a common problem.

At low tide, nearly half of Great Bay is exposed as mud, soft and full of life.

Doyle Fellow Maggie Eid and her collaborators venture into these muddy fields to identify and catalog the creatures living within. From detritus to debris, everything is documented, offering insight into how bottom-dwelling communities are shifting alongside the habitat.

During low tide, around 50% of Great Bay's exposed surface is mud.

In another corner of the estuary, Doyle Fellow Jacob McDaniel is looking for a very specific critter: the blue crab (Callinectes sapidus). Traditionally a mid-Atlantic species, these crustaceans are now showing up more frequently in northern waters. Jacob is deploying handmade traps to track the spread of blue crabs throughout the bay, and is testing larval nets made from PVC pipe and repurposed air conditioner filters, a DIY solution to monitor a dynamic, fast-moving species.

Great Bay is changing, and the Doyle Fellows are exploring these changes through techniques in marine science at JEL.

Together, these emerging scientists represent a new generation of marine researchers working across disciplines to understand and protect one of New England’s most critical estuarine systems. Supported by NH Sea Grant, the Doyle Fellowship gives students the chance to step directly into the rhythms of applied coastal science. At JEL, they aren’t just observing change, they’re part of it.

Beyond their research, the Doyle Fellows are connected by a shared sense of purpose, each called not just to study the ocean, but to protect it. Their bond extends past the lab bench, rooted in a deep emotional connection to the water and the life it holds. In conversations, in fieldwork, even in quiet moments by the bay, their commitment feels less like a job and more like a responsibility driven by wonder and care.

About the author

Talia Katreczko is currently an Undergraduate Student at Tufts University, and spent the summer of 2025 working as a Science Communications Doyle Fellow with NH Sea Grant.